Join us for conversations that inspire, recognize, and encourage innovation and best practices in the education profession.

Available on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Google Podcasts, and more.

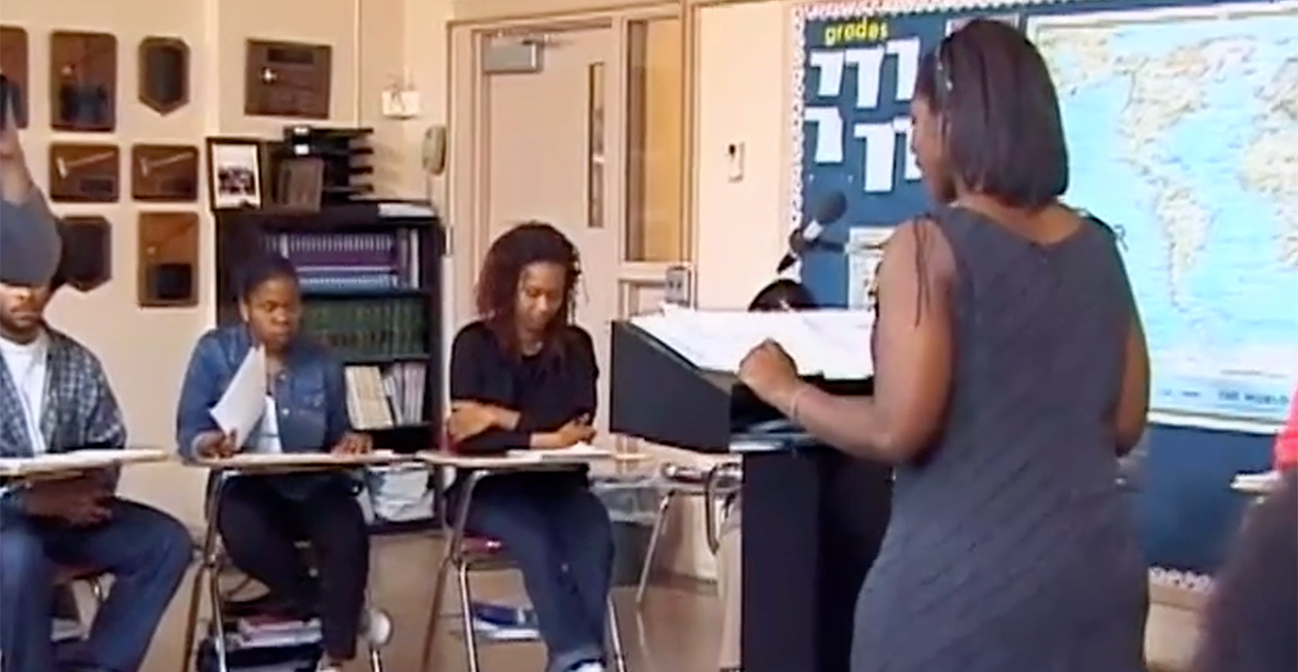

Matt Johnson, who has been in the social studies department at Benjamin Banneker Senior High School in Washington, D.C., for 10 years, is seen in the workshop video teaching a senior honors-level constitutional law class. (He also is featured in Workshop 4, teaching a lesson in AP comparative government.) In these interview excerpts, he discusses why he uses constructivist teaching methodologies and their connection to civic education. The lesson involves small student teams presenting both sides of an argument to a panel of Supreme Court Justices. The case is a hypothetical one developed by the teacher that focuses on the subject of the constitutional rights of students.

Matt Johnson: This lesson has a lot of positives. There’s the responsibility of each student to come up with a brief of a case, so they’re going to have to get to know at least one case thoroughly. Then they have to apply that case and others to a situation that we have no answer to. The Court hasn’t come out with opinions yet on these hypotheticals. It involves teamwork, working with other students, and coming up with an original argument. I think all of these things, with the verbal communication, are positives. This activity puts a lot of responsibility on the kids. They’re the ones who are really taking the material and going with it.

Matt Johnson: This lesson is a culminating activity. It’s not something that’s going to be foreign to these students. They’ve done this kind of thing before. This lesson reinforces a lot of the activities we’ve been doing all year. We like to discuss the Supreme Court cases and get the students thinking about why the Court ruled [in a particular] way [and] what might have changed in 10 years to result in the Court reversing the decision.

Matt Johnson: This lesson incorporates many different methodologies. I have students doing individual work, writing, and analyzing primary sources. I have cooperative learning [and] oral advocacy skills. A more traditional final skill is taking a final exam.

I chose to use a simulation for this activity, in part because it just lends itself perfectly. There are so many different hypotheticals that you could come up with and it gives a chance for these kids to really play with this material and be creative. It is a law class, so we might as well have a moot court. The students in this class have all participated in a citywide moot court competition, but the kids still need to understand how to brief a case–what’s important to look for–so there have been some lectures, some direct teaching, to get kids focused on how you read a Supreme Court decision.

I’d like to think that kids are learning more with the approaches I’ve used. Not just in test scores but in questions and answers a couple of weeks later because they’ve done more than just study for a test. They’ve actually used the material in creating an op-ed piece or drawing a political cartoon. Whatever we’ve done, their hands were involved in the final outcome.

Matt Johnson: The biggest challenge will be the quality of the briefs that are made by the students–whether they get the big picture and the big issues involved in each Supreme Court decision. Then, I think a challenge will be having the kids really put solid thinking into the arguments they make before the Court. At the same time, the judges have to take their role seriously. That’s one of the reasons I have some requirements on the worksheet that has to be filled out. I need to direct them into what I think they should be focusing on.

Matt Johnson: When I say ‘worksheets’ I’m not talking about something that I’ve Xeroxed out of a textbook. My aim was to direct them in what I assume would be a logical way to attack this hypothetical. These are questions that I pose, directions that I want the students to walk through. So, for example, for the lawyers’ worksheet, the first question is, “What are the three main arguments you want to make in your case? What do you think the three main arguments are that the opposition will make?” Then I ask them to actually cite the three most valuable cases (it varies, actually; it may be five depending on the amount of precedent that’s out there). Then I’m going to ask them to write out a two- to three-paragraph opening statement for their position. The idea is they’re going to have a limited amount of time before the Court and they’ve got to use it wisely. I really feel like if I don’t force them to do that they may go in a different direction. I’d like them to be prepared.

Matt Johnson: I try to use questioning on one level as a way of just checking in and seeing what kids are thinking about and finding out. It’s like a mini-review activity, with one, two, or three kids. You start small and build your way up. It may be a way to hone their minds into what I think they should be thinking about. It’s a good way to check on prior knowledge [or] to see if they’re really focused on what we’re doing right now. You can even use it as a way to guide the kids, as you throw out some new hypothetical questions to get them thinking about what they’re working on right now.

Matt Johnson: One of the challenges that you encounter every time you get kids into groups is the dynamic within these small groups. I’ve hopefully paired them off so that the group will work together. There are strong and weak personalities mixed together and they have the material in front of them so it’s not a question of going out and having to search. Getting them to agree on a position, on an argument, a philosophy, may be difficult, but that’s not necessarily a bad thing if they’re talking and engaged.

I think a lot of the groups are struggling with what cases help. Their first reaction is, “There aren’t any cases that support our position; they are all against us.” You really have to move the kids to think about taking anything that’s out there and figuring out a way to apply it to their side. Their initial task is to come up with an argument, and then find material to support it. Once you do a little Q and A with them, and actually bring up cases, they start to see that there is material out there. Even a case that, on its face, goes against their position [has] pieces of it they can use.

Matt Johnson: I’ll be able to gauge whether this is moving successfully by the amount of questions and the quality of the questions that the kids are asking. Initially there’ll be lots of questions: “What do you want us to do? How are we supposed to fill this out?” After a while the questions will cease, and as I walk around and eavesdrop, I’ll be able to gauge by the discussion within each group. They have an assignment that is doable so I don’t expect a big frustration factor.

Matt Johnson: One of the difficulties in getting kids to work in groups is breaking down [the attitude that] “I’m just doing work for myself.” There’s not a lot of group learning, perhaps, for some of these kids in the years before me. So I will give one person the role of the recorder, another person will have [another] particular duty. They have to work together. As time passes, I drop some of those formal roles and it’s the end product that kids have to work on. I let them figure out how they’re going to get there.

One of the things I’ve learned over the years is [that] you have to give each student an assignment. At least for seniors, I’ve found that if you don’t, the burden falls on one or two kids in the group. My hope is you get kids to work together, but the finished product is an individual assignment. Otherwise, there’s no incentive to work for some kids. It sounds terrible to say, but there are students who will just shirk their responsibility on to somebody else.

Letting go in the classroom is at first difficult. When I first began teaching, I guess I was somewhat trained not to let go. If you let go, management becomes a problem, but I found that [being in charge] was a lot more work. I’m not saying I’m lazy, but it was always me [saying], “You guys have got to listen to me, listen, listen, listen.” Kids don’t always want to listen–they want to get their hands dirty. They want to get into the material. If you give them something meaningful to do and you say there are repercussions for not doing it–you have to give grades–it’s not that hard. In fact, to me, it looks like I’m only teaching 10 kids when you have 10 groups as opposed to 30 kids. I think putting kids in groups really makes management easier and it’s really more fun. I know those 30 kids from putting them in groups. If I just looked at them like one block of kids, I would never break down any real walls between me and them.

Giving kids a lot of independence and ownership puts more responsibility on them. There are too many classrooms where I’m responsible for the message; they’re responsible for taking down my thoughts. That is too reactionary. They are just following what I say. I’d rather have them explore and work with the material. I find that these kids, especially, are very creative. If you give them the opportunity to show you what they can do, the sky is the limit. If I gave them everything they needed to produce, I’m just patting myself on the back.

Matt Johnson: When I start the school year and I put together the first groups for an assignment, I will be very random in how I do it. I just know names and I don’t really know the kids yet so it’s really an opportunity for me to learn a lot about the kids. That first assignment tells a lot–who works well together, who approaches groups with a positive attitude. I take notes and keep track of who works well together and who doesn’t. At the beginning of the year, I will try to keep the sexes evenly represented in each group–but that’s about it. As the year progresses and I start to fine-tune my groups, sometimes I’ll say, “Do you guys want me to put you in groups, or do you want to pick your own groups?” A lot of times, the kids want me to continue to control who is in what group. At that point, I think I can group kids pretty well. I’ve watched that over the course of a couple of months.

[It] was easy for me to put these kids together because I really feel that I know these 30 kids pretty well and know who will work well with others. When I was putting [these] groups together, I looked at spreading what I would call the more dominant, at least verbal, personalities throughout the 10 groups and trying to put kids [in each group] that I have observed throughout the course of the year as really having been consistent in their approach to the class, so that every group had somebody that I would say knows the material pretty well. That’s about it. Try to split the boys and the girls up so that there’s not any one group that’s all boys or all girls.

If I wanted to just give the kids information, I don’t think I’d bother with groups. It’d be so much easier for me to just [say], “Here’s the information. Here’s what I want you guys to know. Memorize it for the test on Tuesday.” These kids are smart, and they’ll come up with some novel ideas and novel approaches. I’d be doing them a disservice if I said, “Here is the argument I want you to make in this moot court.”

The group [arguing for Otis Bewear, the petitioner, against the Banneker Student Government Association] really has a pretty strong command of the cases and the appropriate materials they need. They’re three fairly strong personalities and three very articulate students. My only fear is that they won’t share the spotlight, but I think they’ll work well together. They’ve all been in moot court and done very well. They know what’s out there and I know they’ll come up with a pretty strong argument. When I observed [them], they were initially trying to figure out what position to take in their hypothetical and struggling with finding cases that supported their position. I had to sort of move them in the direction of taking cases that on their face hurt them, but turning them around and figuring out a way to either say this doesn’t apply or the language in that decision actually helps you. So they were working through the precedents and then starting to put together how they would approach their oral argument.

[The students representing the respondent, the Banneker Student Government Association] are both quiet in the classroom, but when they get together and it’s more one-on-one, I see those two as very hardworking. [One] is always surprising me because she’s ready for class all the time and [the other] is very quick to voice her opinions and she’s usually pretty accurate.

The group [representing the petitioner in Sloan v. the District of Columbia Public Schools] had a little trouble getting started because they are all similar personalities. They are a little quiet. They’ll do their work, but they’re not big on sharing, so they have to get over that and work cooperatively. All three of them are capable. It may be a question of who is going to speak first, though. I don’t think that anyone will volunteer, but once they get the ball rolling, I think they’ll be pretty strong.

[The students representing the respondent in Sloan v. the District of Columbia] are interesting. That’s the only group that has a junior, but she’s a pretty strong-willed student. [A second member] is a very articulate young man who can pick things up quickly. He knows the cases and so does [the third member]. An issue in that group [may be] not letting [one member] dominate the discussion. My hope is that they will all participate. I know they will in the putting together of the argument, but [one member] may hog the spotlight a little bit. I was pleasantly surprised. They took the hypothetical and immediately starting identifying cases that helped them, which was maybe part of [one member’s] leadership. When I went over and observed them, they were moving along, identifying cases, and starting to immediately think of an argument. That hypothetical threw them off at first. They didn’t understand the voucher issue and why a parent would be opposed to the vouchers. Once that was explained to them, they saw what they needed to do.

Matt Johnson: One of the things that I might do differently–and it would help save time–is think twice about having every single student in a class this size give their briefing of a case. I would require them to type it up, distribute it. But I might not ask all 30 kids to stand up and present. That took a long time and it may not be necessary. It’s a reinforcement of verbal skills and presentation skills, but for the sake of the total class, I might just select some kids, volunteers, that kind of thing.

One of the questions I ask the kids at the end of the lesson is, “Was there enough factual information? Did they need more to argue this case effectively?” If I was going to go back and change anything, I might add some more information to the fact pattern to give kids some more things to latch on to.

Matt Johnson: The lessons that I try and get the kids involved with force them to take on the material, whether it is a simulation or whether I’ve had kids actually redistrict a state to favor one party over another. I try and get the kids really engaged. I think by doing this kind of work, some of the more quiet kids, for example, have been forced to voice their opinions, to think about and react to controversial issues. The issues in these hypotheticals not only relate to them as students, there’s also a parental twist to it. Many of them will be parents with high school-aged kids someday. It’s forcing them to think about their rights, think about the Constitution. If it was just me lecturing to them, they might not develop any kind of passion for this. Even the quietest kid has to do something now in class. Hopefully that’s getting them thinking about being active.

These teaching techniques include so much participation on the side of the student. That’s really what we want people to do–participate in the civic process, the political process, the community process. I think by teaching this way, I’m reinforcing what it means to be a good citizen here in the United States.

Matt Johnson: The students’ presentations were what [I] expected. The student who was briefing the case was knowledgeable of the important issues and facts, the rationale, and the Court’s decision. The students in the audience asked thoughtful, provoking questions. When they broke into groups, I saw some real attempts to frame arguments and go through the cases and cite precedents. I could observe kids asking questions of one another, searching through their materials looking for the appropriate cases to cite. So I thought it went very well.

[During] the Q and A from the kids to the presenters there were a couple [of] very insightful questions. When I asked questions of the class, I was happy to see that the kids knew the answers to some of these key concepts that the Court has put forth. That tells me that they understand what their rights are, but they also understand the logic behind some of the limitations to their rights.

[During Activity 3] I would have liked a little more discussion of some of the cases that the kids were asked to review, but I think it’s pretty easy for them to get stuck on the merits and not worry so much about precedent. I thought the interaction between the Supreme Court Justices and the two lawyer teams was very energetic and got at some good issues. It surprised me a little bit that these guys would be in favor of supporting vouchers. The First Amendment is pretty sacred to these guys, and not favoring religious schools over public schools. I think they have their allegiance with public schools. By the same token, this is the population that would benefit in a lot of ways from a voucher system. They are giving kids, giving parents a choice. When they actually deliberated, they decided the opposite way. Each offered their opinion and then they voted and they changed.

Matt Johnson: This case brings up a lot of interesting issues. Clearly, First Amendment, establishment clause violations brings up choice, brings up funding for schools. The establishment clause prohibits Congress from passing any laws that protect or promote one religion over another to establish an official religion. This hypothetical pushes that a little bit. If state dollars are being used to fund religious schools, is the government establishing an official religion? There aren’t that many cases that the kids have to use to argue this type of hypothetical. You heard the Lemon case quite a bit, and you heard the West Virginia v. Barnett and the school bus case. It is an issue of fairness and equality and education–a very sacred thing for so many kids.

Matt Johnson: I try to stay neutral because I don’t want to color any of the kids’ arguments. I want them to feel free to throw whatever argument they want out there, [but] I don’t know if I stay neutral. I’m sure there’s body language, comments, word choices that I may employ that tip my feelings on a situation. [In] the hypothetical, I tried to use as neutral language as possible. I tried to balance it out. I tried to explain the petitioner’s point of view and give some evidence for the respondent’s point of view. If they perceive me as coming at a situation from one perspective, they may want to argue to be on my side. It’s important to give the kids the opportunity to take the argument anywhere they want.

Matt Johnson: Prior to becoming a teacher, I worked as a legislative researcher for a law firm and enjoyed that quite a bit, but really felt like I wanted to do something where I was in charge of my day-to-day work. I thought nothing could be better than teaching where I really have my own little corporation, so to speak.

Having worked in the private sector before becoming a teacher, and especially working for a law firm, I had an appreciation for what goes on in the legal field and paid a lot of attention to matters on Capitol Hill. So I brought to the classroom a practical understanding and knowledge of those two fields. As far as civic education goes, I have been a big fan of teaching kids the importance of being involved in our society and in the political process.

When I first began teaching, I think I fell into the trap of a lot of new teachers. It was teacher-centered: “Look at me, I’m in charge. I’m the expert. You guys will take notes and you’ll learn from my wisdom.” That took awhile to lose as a teaching practice–[which I did] on the job, watching other teachers and letting go. Once you start to let go, it makes a big difference. You realize that it’s a very successful approach. I think the point I realized it was time to change wasn’t the overwhelming snoring sound I heard when I would lecture, but certain lessons I knew were not getting across to the kids. I could tell by test results. We would prepare for a mock trial my first year and we did horribly. I wasn’t letting the kids get into the material enough. I was trying to tell them how everything should look and arguments that they should make. I started to realize that this group of kids really has a lot of ability and you’ve just got to let them go to the material and they’ll do some amazing things with it.

One of the things I did was think back to when I was a high school student. I started to reflect on what I remembered from my four years of high school and it was when we as students had been given an opportunity to create something. I started to say, “That’s what I want kids to remember down the road, a couple of years from now.” I thought that I had to come up with simulations. There were lessons already out there, so I just started putting things together myself and immediately I enjoyed teaching more and I think the kids enjoyed the class more. That made a big difference.

Matt Johnson: The textbook for this class, We the Students, which comes out of American University Law School, is a nice collection. It is the cutting edge Supreme Court cases that deal with students’ rights. It covers the First, Fourth, [and] Eighth Amendments to the Constitution and their incorporation into our public schools. [It] digests the cases and abridges them.

I use the textbook throughout the year as the source for a lot of the Supreme Court cases. I will assign a case to read. Usually I will give them a quiz on what they’ve read. I find if I don’t, and the kids know there’s not a quiz, they may not read it. The questions are taken directly from the book. Once the quiz is over, we start talking about the real issues in the case. We relate it to previous cases. I may throw a newspaper article at them from an issue on students’ rights related to [the case]. It’s really the starting point and it’s a great textbook for that purpose. For the assignment they had to do for the first day of the lesson, they had to go beyond what was in the textbook because it’s not full text.

Matt Johnson: I have tried to stay up to date with teaching methods and content through attending a few workshops. Since enrolling as an AP teacher, I’ve been to a few content-driven workshops, but AP [also] tries to give you some teaching tips on how to get this stuff across. That’s been the bulk of my professional development. As far as content goes, I’m in a great city. There are a lot of good things to read, a lot of things going on, that make teaching government absolutely a wonderful experience. You can make teaching government wonderful anywhere but you may have to buy a Washington Post or a New York Times, and you probably want to watch C-SPAN now and again. You’ll have the advantage of being in a state, so that could make things interesting, too.

Matt Johnson: I think I model civics education by being neutral, by trying to get all the sides out on an issue, by exposing the kids to–for lack of a better word–some of the negatives about our Constitution and our history. I’m not afraid to tackle controversial issues. I’m hoping that by being honest and up front with the kids, nothing’s beyond approach, and everything’s up to being questioned. I don’t think we just dwell on the negative, but especially with a population of minority students, you can’t just focus on positives; there are a lot of negatives. If you’re going to be honest, you have to talk about some of the negative chapters in our history. If you don’t, the kids are not going to believe you and they’re not going to want to listen to you. You’ve got to tell the truth, but it seems as though these kids have taken that knowledge, and because they now know more, they no longer feel like they’re victims. I think if you show the negatives, then as the teacher you may have to introduce some positives and there are a lot of positives. Then you can cover the subject fairly.

In the law class, when you start talking about students’ rights, everybody sort of leaps on the Tinker v. DesMoines case–a great decision–and the kids understand what the logic of the Court was in that particular case. Then you fast-forward to the Hazlewood v. Kuhlmeier case, and that’ll generate a lot of discussion. I think a lot of kids understand the logic of the Court in giving an administration, a principal, some power to control what’s done in their school. The kids know they’re here to learn and that’s where the restrictions can come in, if you disrupt the process. That’s positive and negative, but it’s being truthful, it’s being honest. It doesn’t mean that every decision an administration makes is the correct one, but you’ve at least shown the kids the logic behind the thinking of the Court, and they can then apply that to current issues that come up.

I try to be non-partisan. I trust the kids. For example, in one class we had to pick a fifth country to study. I didn’t have a vested interest in any, so I threw it out to the class and they voted. I’ll give the kids an opportunity to select their own groups. I do try and work with the kids. I’ve got to be with them for 10 months. I don’t need an overthrow early in the school year, so I try to be democratic.

Matt Johnson: The kids understand and can identify the three branches of government. They know the Executive branch, what their “responsibility” is; the Judicial branch, they check the laws; the Legislative branch makes the laws; and the Executive enforces. But you ask them what that really means, and they don’t have a clue. So, they could fill in the blanks on a blueprint of our government, but that’s about the extent of their knowledge. Getting them to think about what these three branches do is important, and the relationship between the Federal and the state is lacking, too. Federalism is a concept very few kids understand.

One of the challenges in the District [of Columbia] is explaining the concept of Federalism. With the District being the unique Congressional territory, the idea of “state” is very hard to sink into these kids. We’re just really a city, anyway, but there is State authority, and then there is the Federal authority. They’re very blurred here.

The other area of difficulty sometimes is explaining the powers of the bureaucracy. It’s kind of a dull subject, but they have a lot of authority. Kids don’t see that power.

Matt Johnson: I think I’ll know if I’ve been successful in a couple of ways. One would be a successful score on the AP exam. Two, if kids come back in a couple of years and show me their voter identification card, or if I talk about current affairs with them [and] they’re keeping abreast of what’s going on, that’s how I probably will know. They don’t all have to become lawyers or politicians, as long as they’re active.