Join us for conversations that inspire, recognize, and encourage innovation and best practices in the education profession.

Available on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Google Podcasts, and more.

The Lesson Plan section contains everything you will need to fully understand the featured lesson. It has the following sections:

Teacher:

Alice Chandler has been a social studies and special education teacher at the Duke Ellington School of the Arts in Washington, D.C. since 1994. She holds a Master of Arts in special education from the University of the District of Columbia, a Bachelor of Arts with a major in sociology and a minor in history from Howard University in Washington, D.C., and has done graduate work in American history at Howard University. For a number of years, Alice Chandler worked on the Integrated Curriculum Development Project at Ellington, developing social studies lessons for a Smithsonian Institution-developed curriculum. She is also a consultant to the local affiliate of the National Writing Project.

School:

The Duke Ellington School of the Arts is a public magnet school within the District of Columbia Public Schools that began in 1974 to provide an environment where students of color could gain tools to achieve cultural equality. In addition to seven arts disciplines–dance, literary and media arts, museum studies, music, theater, technical theater, and visual arts–the school offers a full academic college preparatory program. Students come to Ellington with various levels of academic achievement; this class includes several special education students. Ellington provides classes ranging from basic reading and math refresher courses to college-level English, pre-calculus, advanced U.S. history, and advanced biology. Ellington’s social studies department is reputed to be one of the best in the city. Because the school is in the middle of Washington, D.C., its students are probably more exposed to politics and political activity than most high school students, including seeing Washington’s monuments on a regular basis, passing through the area of the city in which most foreign embassies are located, witnessing numerous traffic stops as the President and other dignitaries pass through the city, and seeing and/or participating in a variety of political rallies.

Course:

U.S. Government is a one-semester course for seniors taught on a block-period schedule. Alice Chandler often organizes the course in what she calls “portfolio mode,” a series of papers or examinations that the students complete during an advisory period. In one advisory period, she might focus on the U.S. Constitution, in another–on political parties. Teachers at Ellington are encouraged to integrate academic subjects with the arts. During the advisory period prior to this lesson, for example, students had to choose a book and/or video that dealt with both the United States government and the art form they are studying. A theater major, for example, might have done a project on Paul Robeson that explored both his acting and his political activism.

This lesson addresses the national standards listed below.

From the Center for Civic Education’s National Standards for Civics and Government (1994):

Foundations of the American political systems: Students should be able to explain the importance of shared political and civic beliefs and values to the maintenance of constitutional democracy in an increasingly diverse American society.

Relationship of the United States to other nations and to world affairs: Students should be able to evaluate, take, and defend positions:

The roles of the citizen in American democracy: Students should be able to:

From the National Council for the Social Studies’s Expectations of Excellence: Curriculum Standards for Social Studies (1994):

Civic Ideals and Practices

Overview

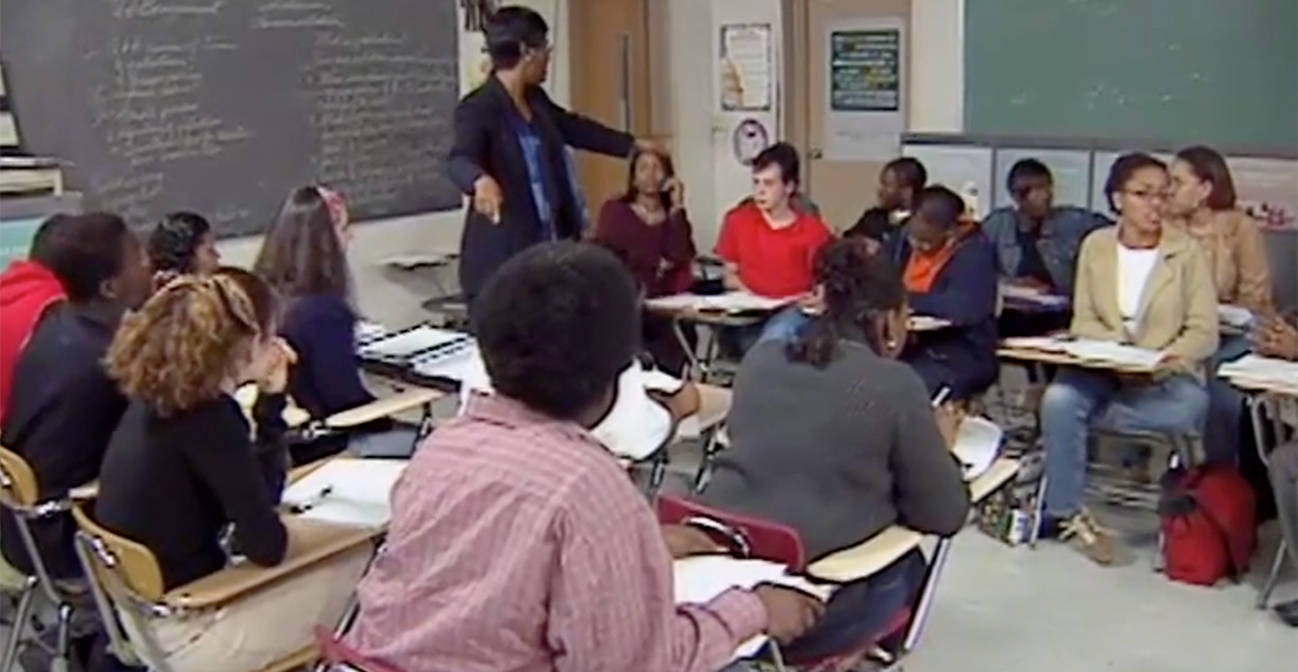

The students in this lesson are seniors at the Duke Ellington School of the Arts, a public magnet school in Washington, D.C., that has a strong commitment to integrating the arts with academic subjects. U.S. government teacher Alice Chandler, who finds Socratic questioning and Howard Gardner’s theory of multiple intelligences particularly useful in an integrated arts environment, has developed a lesson in which students create a Museum of Patriotism and Foreign Policy. Over three days, the lesson alternates between whole-class discussions, in which the use of Socratic questioning is evident, and committee work, in which students determine what will be placed in the museum, using their particular art major as the basis for their choices. The conclusion of the lesson shows the students’ presentations, including dance, music, theatrical performances, and visual representations, along with rationales for their selections.

Goal

The goals of the lesson are for students to discuss and define the word “patriotism,” discuss and decide what they think U.S. relationships with the rest of the world should be, and select artifacts for a Museum of Patriotism and Foreign Policy that are relevant to the concepts of patriotism and/or foreign policy. Students are also expected to demonstrate their understanding of patriotism and foreign policy through one of the arts.

Planning

Earlier in the semester, students read several Supreme Court case summaries (see Lesson Materials below) that relate to patriotism, including Minersville District v. Gobitis (1940), West Virginia Board of Education v. Barnett (1943), and Johnson v. Texas (1989). Johnson v. Texas, in particular, which decided that it was within a person’s First Amendment rights to burn a flag, generated a great deal of discussion and controversy among the students. The class also discussed how various members of the school community, which includes students born outside of the United States, define patriotism, and came to understand that patriotism might be viewed quite differently in other countries than it is in the United States.

Activity 1: Large-Group Discussion on Patriotism and Foreign Policy

This initial discussion should set the foundation for the lesson as well as review concepts that have been previously discussed. Stimulate a discussion with the following questions:

Use Socratic questioning (see Essential Readings) to help probe students’ understandings and challenge their assumptions, and to prompt them to fully explain their ideas.

Activity 2: Area-Specific Committee Meetings

Create a Head Committee and four or five other committees, each consisting of three to four students. Each group should have a recorder and a spokesperson or reporter. Students should choose their own committee leadership at the first meeting of the committee.

Using teacher-provided supplementary materials (see Lesson Materials below), the Head Committee will begin to:

Because of the complexity of this assignment, the Head Committee will probably need to work on this assignment over several days.

During Activity 2, all other committees will begin to:

Give all students the rubric (see Assessment below) against which their work will be judged and discuss as needed. Remind all groups to use the information gathered from earlier research and the Supreme Court cases discussed in class. For homework, students should seek out artistic examples for consideration by their respective committees. Students might also look for examples of how the arts have been used to promote patriotism.

Activity 3: Warm-Up Activity on Patriotism and Foreign Policy

Using Socratic questioning in a whole-class setting, discuss what students feel the United States’s role should be in disputes that affect our foreign policy, i.e., health issues in Africa. Questions to help in directing the discussion include:

Activity 4: Committees Finalize Museum Selections

Each committee should try to reach a consensus on its museum selections and prepare the selection rationales. Any remaining time should be spent rehearsing the presentation they will make to the class. Some of this work may need to be done as homework.

Activity 5: Committee Presentations

Begin with the presentation of the Head Committee’s proposed design for the museum, along with the timeline, selections of individual events/people from the period that depict a definition of foreign policy, and artistic representations of patriotism. Proceed to the presentations of the other committees concerning their definitions of patriotism and their creative expression of that definition. Remind students, as needed, that each selection needs a one- to two-sentence explanation of its meaning in relationship to the theme. Use the rubric to take notes on each group’s presentation.

For homework, assign a brief essay in which students communicate their personal reflections on patriotism and foreign policy.

Scheduling and Adaptations

Alice Chandler pursued this lesson over a three-day period and was able to take advantage of block scheduling. She covered two activities per day, alternating between whole-class discussions and committee work. Time was the biggest challenge, however. In hindsight, she felt that students would have had a better opportunity to bring all elements of the lesson to closure if they had had more time, perhaps by spending five days on the lesson. Other teachers using this lesson should take into consideration that Ellington students often are in performances outside of school, a practice that cuts into the academic schedule significantly at different times of the year, and often makes it difficult for them to complete homework assignments.

In terms of adapting the lesson for students of different ages or with varied abilities, note that this class includes several special education students, who are able to work from their own strengths due of the nature of the lesson. Committee assignments provide built-in opportunities to draw on students’ different intelligences, as defined by Howard Gardner’s multiple intelligences theory (see Essential Readings). Alice Chandler stresses the need for teachers to find out about their students’s particular skills and interests before using a lesson like this, so that they can connect new ideas with prior learning experiences and interests. She also points out that this lesson was taught almost at the end of the semester, so she had had ample time to learn about individual students.

Other ways in which the lesson might be adapted include the following:

Below you will find the assessment rubrics Alice Chandler used for her lesson on Patriotism and Foreign Policy. You can download these documents and print them out for your use.

Below you will find the materials Alice Chandler used for her lesson on Patriotism and Foreign Policy. You can download these documents and print them out for your own use.

Supreme Court Cases

Listing of Terms, People, Events for Use by Committees (PDF)

Web Site Recommendations

Below you will find additional resources pertaining to this lesson.

Grossman, David and Mie-hui Liu. “Citizens: The Democratic Imagination in a Global/Local Context,” Social Education, Vol. 64, No. 1, pp. 48-53.

Hess, Diana E. “Discussing Controversial Public Issues in Secondary Social Studies Classrooms: Learning From Skilled Teachers,” Trends in Research in Social Education, Vol. 30, No. 1, January February 2000, Winter 2000, pp. 10-41.

Joseph, Paul R. “Law and Pop Culture: Teaching and Learning About Law Using Images From Popular Culture,” Social Education, Vol. 64, No. 4, May/June 2000, pp. 206-209, 211.

National Council for the Social Studies. “Fostering Civic Virtue: Character Education in the Social Studies,” a position statement of NCSS. ©1997 National Council for the Social Studies. Prepared by the NCSS Task Force on Character Education in the Social Studies. Approved by NCSS Board of Directors, Fall 1996.

Stevens, Robert. “A Thoughtful Patriotism,” Social Education, Vol. 66, No. 1, January/February 2002, pp. 18-24.